For a few weeks during November and December 2016, commuters exiting Rotterdam’s striking central station encountered a series of billboards situated along Kruisplein – the plaza that leads from the station southward toward the river Maas. The billboards depicted 12 alternative visions of a future Rotterdam. They were commissioned by the New Institute (Het Nieuwe Instituut) and were created by local designers.

(The billboards along Kruisplein)

Creating imaginary urban futures for public consumption is not new. New York’s World Fair of 1939-40, for instance, featured not one but two futuristic cities called Democracity and Futurama (I’ve written about the Fair here). More recently, the Museum of Vancouver, in collaboration with Urbanarium, held a similar exhibition from January to May, 2016, titled Your Future Home. While the Vancouver exhibition addressed fairly technical categories of urban design (residential density, public space, transportation and housing affordability), the visions located outside Rotterdam’s central station engaged with a mishmash of technical and aspirational categories such as inclusivity, new technology, sustainable prosperity, innovation, mobility, bottom-up, quality of life, circular city, vacant buildings, densification, energy transition and urban streets. Both exhibitions, however, were created by professional designers and architects, and were meant to stir discussion about urban design.

The exhibition came in response to a specific policy proposal: Woonvisie 2030. The controversial proposal sought to reduce the city’s stock of low-cost housing units by 20,000 and replace them with 16,000 higher-end units. Citizen groups that opposed the proposal forced the city to hold an advisory referendum on November 30, hoping that it would compel the city to re-evaluate the proposal and galvanize a strong opposition to what they saw as yet another act of gentrification in a city that lost close to 30,000 low-cost units since 2000. Alas, their plan failed. While opposition to the policy won a majority in the referendum (72.5%), turnout (16.9%) was lower than the minimum required to validate the referendum (30%). As consequence the policy could be green-lighted without further input from the public.

As the exhibition’s curators state, the 12 visions sought to expand and add nuance to the debate on the proposal.

The exhibition does not seek to provide advice on whether to vote for or against the City of Rotterdam’s urban development vision, but aims to challenge the city’s residents to think about how they want to live in the city fifteen years from now and thereafter. Alongside statistics and policy resolutions, it is important that designers’ visions are also part of the debate about something as important as the city’s future, especially in a city with such a rich tradition of experimental urban design. (source)

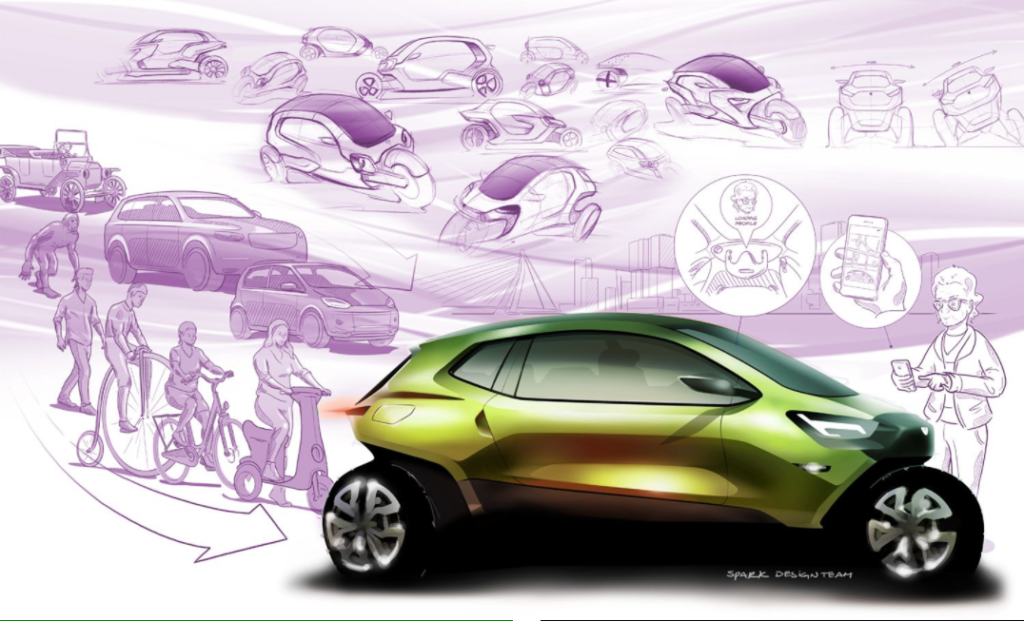

Looking at the different visions I was struck by several features. First, five of the twelve were driven by technological innovation. Take for instance this vision by Spark Design & Innovation:

(source)

Not only does this vision address the theme of mobility through a single technological driver (the electric car), but it also seems much too close to the present to actually evoke a radically different way to imagine the city. Further, while it adopts a narrative that reflects the Dutch values of autonomy and self-sufficiency (according to which electric cars can be seen as the next step in the evolution of bicycles), it neglects other important Dutch values such as efficiency and collectivity (contra Hofstede’s cultural indicators!). Shouldn’t a future Rotterdam seek to correct the mistakes made by its post-war designers and reject the prominence of cars in urban design?

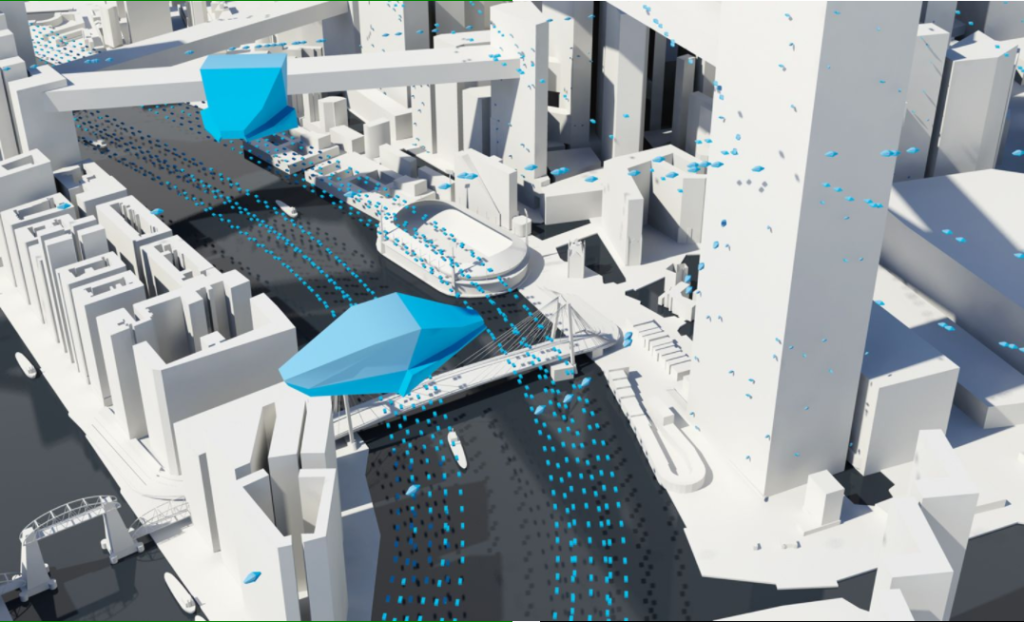

Innovations in mobility drove several other visions such as De Straten (‘The Streets’) by Maxwan Architects + Urbanists (to which I return below), and Skycar City from MVRDV:

The coming decades will radically alter the city: a new kind of metropolis will be born, without roads and without traffic lights. We will park in the sky! The city will become truly three-dimensional! The city will liberate itself from the ground. Urban density will be lifted to a higher level. Welcome to Rotterdam, Skycar City!

But what would such ‘liberation from the ground’ mean for pedestrians? Will there even be pedestrians?

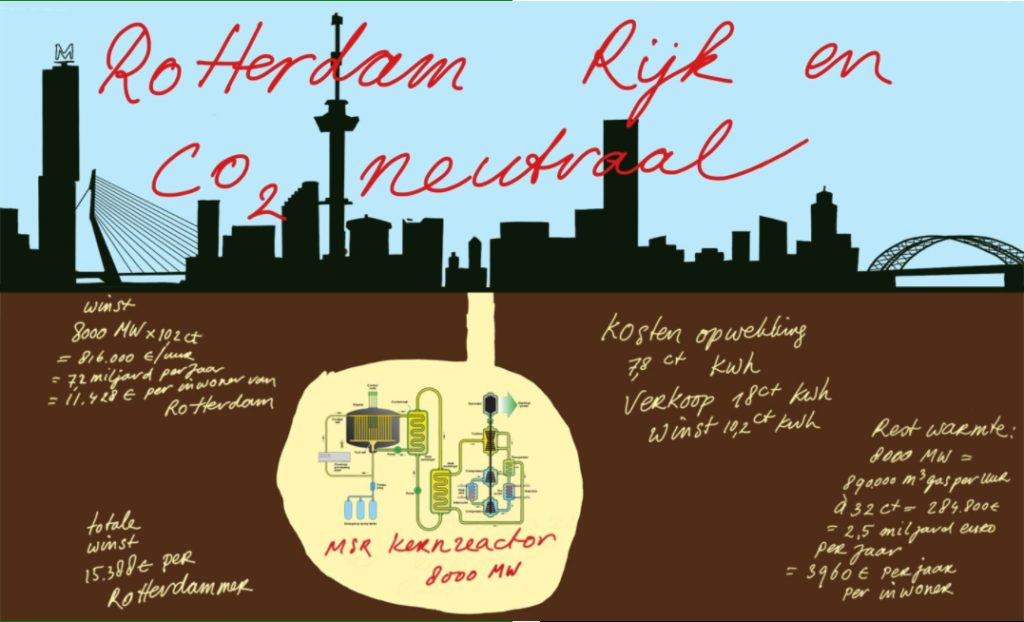

A different techno-utopian future was featured in a vision by Atalier van Lieshout. Here, the city will transcend the (perceived) tradeoff between sustainability and material prosperity and become both by building an underground nuclear reactor that will power all of the Netherlands. The generated wealth, oddly, will then be used to collectivize the harbour, making everyone even richer. But will this reversal of neoliberal economics produce rich individuals or a rich collective? It isn’t clear. It also isn’t clear how happy Rotterdammers will be living on top of a nuclear reactor.

A second striking feature of the visions presented in the exhibition was the degree to which they were relatively pragmatic. Only a few of the visions were flashy and provocative, while the rest seemed fairly levelheaded, practical and, well, Dutch.

Take for instance The Stairwell from ZUS, in which Rotterdam’s empty offices can be turned into housing units by the simple addition of external staircases and useable facades to existing commercial buildings.

Similarly, there’s nothing flashy about the proposal from West 8 urban design and landscape architecture:

The ultimate Rotterdam street is a lively urban street with a mix of living and working and a diverse range of housing, with pavements, trees and the promise of a river. The street and the buildings are raised above the highest flood line. The Maas whispers.

The Happy Street depicted in the vision (and which gives it its name) looks like it could exist anywhere, the only sign of locality is the crane in the background, evidence of the street’s proximity to the port. Nonetheless, this vision integrates an important environmental factor: the street is located above the Maas’s highest flood line (although it’s unclear whether this vision already takes into account the anticipated impact of climate change on the regions waterways). What looks like the standard mixed-use street so popular with current urban designers is set in relation to the river’s natural ebb and flow, albeit, happily floating above the river’s pulse, almost oblivious to the flows that underlie it. “The Maas whispers”, but can the residents of Happy Street hear it?

Much like the previous visions, the one by &RANJ Serious Games assumes that an already existing technology holds the key for a new urban epoch. In this sense, it merely projects the present onto the future.

In the digital city of 2030, physical reality and virtual reality will be fused into a fantastic hyperreality. The city makes room for our imagination: it is no longer bound to the laws of time and physics but can take on all manner of forms. The city is tailored to each individual. It is a playground, a game in which the inhabitants can have unique, meaningful experiences and in which they can make, break and repair the rules.

Turning the city into a playground for its citizens’ imagination strikes me as a very appealing proposition, but the vision is eerily similar to the dystopian world imagined in Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror. Wouldn’t such a gamified, customizable, blended reality end up producing a hyper-individuated experience of the city, one that is antithetical to the kind of urban sociality so many citizens crave? Must we be ‘alone together’ in the city of the future?

As Martijn de Waal argues in The City as Interface (2014), with their emphasis on efficient, customizable experiences, such technological visions conjure a libertarian ideal of urban citizenship according to which city dwellers are approached foremostly as individual consumers. They may be free to “organize life according to their own insights”, but as consequence reduce their involvement and solidarity with others.

As these visions make clear, the arrival of new technologies is expected to create new relationships between city dwellers. But it can also redraw the relations between urban forms and the natural environment – the interfaces between the artifactual and the natural. Take for instance the vision offered by Maxwan Architects + Urbanists I briefly mentioned above:

In a clever homage to the very space in which the billboards stand (the premise of the city’s old zoo, the traces of which can still be found in proximate street names such as Diergaardesingel (‘zoolane’)), the vision features a green city centre made possible “when in a certain sense the car got its own brain”. Nature, in this vision, is invited back into the heart of the city once the car is no longer king in Rotterdam, albeit, it remains visibly and neatly confined. In a sense, nature becomes a complement of the “silent, elegant, almost invisible” characteristic of future cars; more of a trace of the nonpresence of automobiles than an entity in and of its own.

Nature plays a more central role in what are perhaps the two most provocative visions in the exhibition. In Felixx Landscape Architects & Planners‘s vision, the abundance of free renewable energy enables the transformation of the Kralingen Plas (lake) into a phantasmagoric pleasure dome, complete with both snowy and tropical landscapes. Ski-lifts and flamingos co-exist; Jevons’s Paradox be damned!

In this vision nature becomes the material out of which human pleasure and decadence are manufactured. It’s an artificial nature, nature sans nature. It signals the completion of the modernist project – the substitution of nature by manmade objects – the logical conclusion of the Dutch experiment in conquering nature.

In the second vision, Resillience by De Urbanisten, the city is visibly in the process of returning to its original, swampy origins. Monkeys, birds and humans share the re-wilded urban landscape as a sign of co-existence.

We live in a delta

In a city of ebb and flow,

Of to and fro,

Of give and take,

Everyone is welcome.We do our dreaming together,

In a wonderful bath,

Fed by the warmth of the city.Rotterdam is complete

Nothing is lost.

Whatever remains

Is a wellspring for the new.

Nature, in this vision, becomes a marker of a new hybrid urban form. A true symbol of a different urban experience – one in which nature is allowed to breech its confinements in neatly drawn canals, fields and parks. Not a remnant to discard nor a remainder to cherish, but an equal urban force whose presence is as significant as that of the built environment in the background. Without it, something is lost. With it “Rotterdam is complete”.

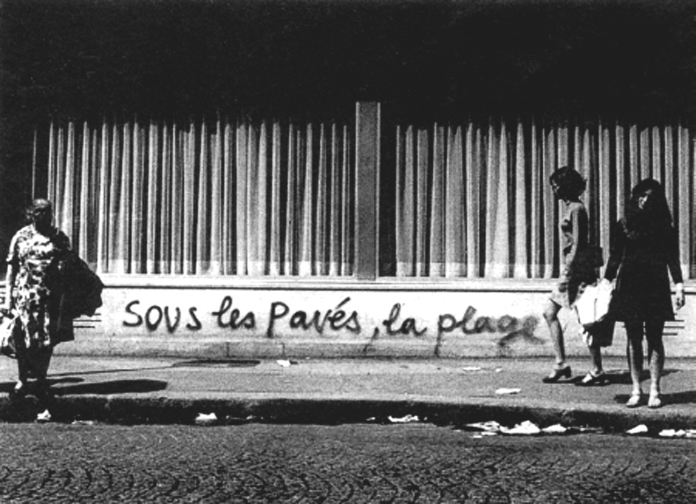

In this sense, this last vision represents not only a new relation between the city and the river that gives it its pulse and livelihood, but echoes the spirit of those anonymous Mai ’68 sloganeers: if we stop trying to repress them, the presence of already existing urban realities can be liberating and transformative. Under the cobblestones, the Maas.

* with thanks to Jotte de Koning for help with translation and to Emma Puerari for sharing a chilly winter’s excursion to the exhibition.