In a previous post on maps I mentioned that Napoleon has commissioned a “bad smell” map of Egypt in an attempt to safeguard his troops from malaria. I first came across this tidbit in an episode of James Burke’s Connections, but others mention it too:

Pamela Dalton mentions the map in an article (warning: pdf) in the Journal of Cosmetic Science, referencing J. Christopher Herold’s Bonaparte in Egypt (1962). Yet a Google Books search of Herold’s text yielded nothing (although it could be due to missing pages in the digitized copy).

Gubler & Wilson mention the map in a book chapter from 2005, but with no reference or attribution.

The map is also mentioned here, and here, but again, with no references. Strange. Very strange.

(Serrement de nez – Serment de Ney / Je jure que ça sent la violette (pun: the pinching of the nose – Ney’s declaration / I swear I can smell violets) by Lacroix, 1805. See original here)

I was pulled back into this wild-goose chase of Napoleon’s alleged map after coming across a recent Big Data glorification piece in The Atlantic‘s Citylab. The piece describes the creation of urban smellscapes from various social media feeds by researchers from Cambridge.

The method is worth recounting: first the scientists went on several “smellwalks” that resulted in a set of olfactory keywords. Those keywords were then used to retrieve geo-tagged social media data (from Twitter, Flickr and Instagram) and create smell maps of Barcelona and London.

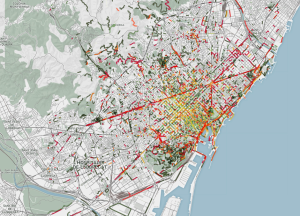

Here’s the one for Barcelona:

(source: Quercia, Schifanella, Aiello and McLean. click to embiggen)

And here’s the one for London:

(source: Quercia, Schifanella, Aiello and McLean. click to embiggen)

After all the heavy data lifting the researchers discovered a pattern: “good” smells are often clustered around green spaces (like parks), while “bad” smells often line major traffic routes. And this led them to conclude that

[…] there is a high correlation between areas with poor air quality and the areas in which social media users detected emissions smells like “gasoline,” “dusty,” “exhaust,” and “car.” Conversely, air pollutants were less present in areas where social media users detected nature smells: “floral,” “lavender,” “grass,” and “sulphur.” The human nose is a powerful thing.

No kidding Colombo!