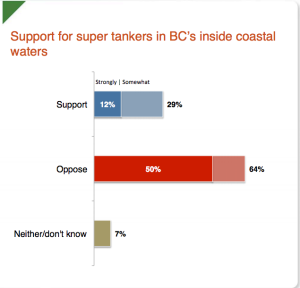

A February poll conducted by Justason Market Intelligence found that “nearly two-thirds majority (64%) of B.C. residents oppose routing large crude oil carriers (or supertankers) through B.C.’s inside coastal waters”.

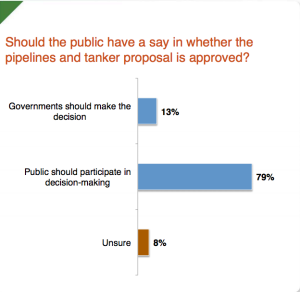

An even larger majority thought that government should take the public’s position into account:

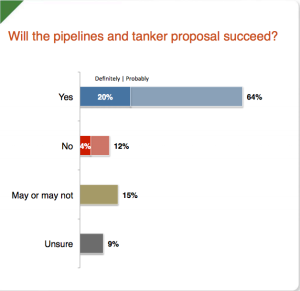

But then, when asked whether they think plans to expand tanker traffic will eventually go through, a similar majority answered that it will:

How do we make sense of these results?

First, it is fairly clear that the vast majority (92%) of BC residents are well aware of plans to transport tar sand product through the province and ship them from Kitimat. Yet while BC residents are roughly split in their position on the Enbridge pipeline project, there is a majority against increased tanker traffic. As Barb Justason notes, “Less than half of B.C. residents support the proposal when we’re discussing just the pipeline. When reminded that tankers are a critical element in their proposal, support drops about 20 points”. The combination of pipelines and tankers, it follows, may present environmental communicators with a potent set of messages to work with. This is especially important information considering plans to expand the Trans Mountain Pipeline (which would multiply the port’s tanker traffic seven-fold), and the current struggle to halt those plans by Burnaby residents. .

Second, and even more important from my perspective, the poll seems to point to an acute lack in political self-efficacy. We know what we want, and we want government to listen to us. But we concede that politics as they are currently practiced in the Province tend to disregard our views. If, then, as French philosopher Jacques Rancière argues, “Politics is primarily conflict over the existence of a common stage and over the existence and status of those present on it” (Disagreement, 1999, pp.26-7), it seems that while we have agreed on the existence of the stage, we have yet to climb on it and exercise our rights as “speaking beings”.

Addendum (July 31, 2014):

A recent poll (pdf) commissioned by the Canada West Foundation (which is supported by Enbridge among other energy companies) and undertaken by Ipsos Reid, found that residents of British Columbia have the least amount of trust in the energy sector (only 20% stated that they trust energy companies). The report states that unlike the case of the mining sector, where low levels of trust may be the result of less knowledge or familiarity with its activities, BC residents claim to be very familiar with the energy sector.

The report concludes that:

Resource industries are recognized as doing well at contributing to the economy and creating jobs. In fact, these were also the top reasons why respondents trust the energy, mining and forestry industries. However, the energy, forestry and mining industries are also perceived to be motivated solely by profit. This suggests that communicating good performance on economic contributions and job creation has a lower impact on improving trust levels, compared to environment, impact on local communities and public health and safety. (my emphasis)