What happens when you allow researchers to enjoy the liberating effects of the imagination? How would the capacity to break from the constraints of the “now” and project different futures open up new and exciting research directions? A recent CFP sent by Daniel Pargman, in preparation for Critical Alternatives 2015, gave Alec Balasescu and me an opportunity for some playful experimentation. Here’s what we came up with (and yes, we are being somewhat ironic):

(work by Douglas Coupland, Vancouver Art Gallery, July 2014)

Universal Sustainability Sensorial Regulation (USSR)

Abstract

The Universal Sustainability Sensorial Regulation system (or USSR) was developed in response to stalled negotiations for a global treaty to curb GHG emissions, and to the catastrophic failure of geoengineering. Building on recent advances in nanotechnology and the consolidation of the Internet of Things, USSR is designed to regulate the human sensorium based on real-time input from atmospheric and machinic agents. Following an expedited process of ethical approval, the system has now been operational for 20 months, in 5 sites on 3 continents. Our initial findings show that as hypothesized, (1) manipulating human thermal comfort levels by only 2°C saved an average of 1500 kW/h and reduced GHG emissions by an average of 5 tonnes annually, per household; (2) initiating higher levels of gluten intolerance in response to global grain shortages proved successful in preventing food riots; (3) while our comprehensive surveys and interviews indicate that human subjects find the system to be relatively satisfactory overall (m=6.4), we are still grappling with what can only be described as overzealous behaviour by machinic agents (OBaMA), resulting in 31 confirmed injuries. We intend to investigate this further by deploying the innovative techniques of machine anthropology.

Research Setting

The conception, development and deployment of the USSR system was made possible by the coalescence of three crucial elements: (1) the emergence of a wide global consensus around the need to develop new ways to adapt to climate change; (2) the availability of unprecedented research methodologies, techniques and tools; and (3) the maturation of a philosophical and ethical disposition within which this research can be justified. These catalyzed the reorganization of academic knowledge into a single, universal science.

Necessity

As the effects of climate change were felt with increased intensity, the global community scrambled to find solutions. However, mired in geostrategic conflicts of interest, international negotiations failed, while existing technologies with GHG reduction potentials such as nuclear energy, were rejected by popular opinion. Some new technologies did not fare better, as a series of colossal failures caused the abandonment of geoengineering, and the insistence of Lockheed Martin to maintain strict control over its patents, prevented fusion energy from scaling up sufficiently. With the growing realization that political and cultural solutions were either too meagre, too slow, or too late, a consensus has emerged: since the primary factor driving climate change is human behaviour – a product of neural and physiological activity, metabolism – human behaviour itself would become the object of action. If we can’t change the atmosphere we must change ourselves.

Means

With the development of nanotechnology, and the ubiquity of smart, sensing, networked objects, scientists are now able to “sense” the world and make digital records of its every fluctuation. Supercomputing technology has broken new grounds in terms of monitoring and managing all this input, generating detailed information about millions of entities in realtime. Deep Informationalization (the lesser evil twin brother of Big Data), has ignited imaginations all over the world, and has given scientists unprecedented powers (such as could only be dreamed of by Francis Bacon or B.F. Skinner).

Ethics

Treating humans as objects of research and molecular manipulation has become much more accepted, due in large part to the popularity of posthumanism. With a view of ontological parity between humans and nonhumans, scientists have been given philosophical license to initiate research projects that mobilize invasive technological innovations in ways that may have been far too controversial hitherto. As the critical discourse of culture, ideology and consumerism was replaced by scientific experimentation and technical tinkering, science stands-in for politics. Marx was replaced by the MRI. Furthermore, the impending end of civilization as we know it, has made the sacrifice of a few “casualties of science” much more palatable. This eased the burden of research ethics reviews and gave researchers practically unfettered access to the very somatic core of their subjects.

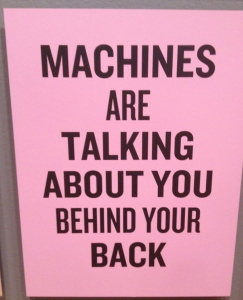

The Emergence of Machine Anthropology

The unprecedented availability and consequent centrality of data has redrawn academic fields and initiated a reorganization of academic knowledge. The academic reform was threefold:

- Multidisciplinarity was replaced by a single universal science. What were once considered separate – even antithetical – disciplines such as the arts and engineering, have now converged into a single, “machine anthropology”. Its hallmark is the treating of all entities through the same methodological lens, extending ontological parity into epistemological terms.

- Knowledge production was extended to include all forms of sensorial perception. What were once considered separate realms – ‘raw’ data and ‘refined’ judgement – are now understood as mere stages in a holistic process of knowledge production. Thus, the human sensorium and the kind of aesthetic judgments it enables, along with machinic sensations and machinic modes of expression, produce a continuous flux of data, whose analysis, development and application has come to replace the lengthy, time consuming, and at times crippling process of peer-review.

- Technology is regarded as both an object of study and as a subject-for-itself that produces knowledge on its own account. Within the emergent machine anthropology, machine-enhanced sensorial perception is treated symmetrically, completing the decentering of humanity’s view on itself.

Here is some fictional research inspiration from others:

‘ICT4S 2029: What will be the systems supporting sustainability in 15 years‘ by Birgit Penzenstadler, Bill Tomlinson, Eric Baumer, Marcel Pufal, Ankita Raturi, Debra Richardson, Baki Cakici, Ruzanna Chitchyan.

‘The Age Of Imagination: A History of Experiential Futures 2006-2031‘ by Trevor Haldenby and Stuart Candy.