One of the conclusions of the workshop I participated in during CHI’14 was that we needed to formulate a collective vision for the future of sustainable interaction design. Under the unwavering leadership of Six Silberman, and after a very quick turnaround, our essay was published in the Sept.-Oct. issue of Interactions, the flagship publication of the ACM’s SIGCHI.

Archives

All posts by roybendor

The New York World’s Fair of 1939-1940 was by most accounts an impressive sight. Occupying 1,216 acres in Flushing Meadows, the fairgrounds were packed with exhibits, rides and stalls divided into 7 distinct zones centred around the phallic presence of the Trylon tower and the ball-shaped Perisphere. In its first year the Fair attracted an estimated 26-million visitors. Admission cost 75¢.

Unlike its predecessors, instead of focusing solely on the achievements of modern science and technology the Fair sought to illustrate a vision of the future. As the Fair’s president, Grover Whalen wrote in the brochure:

From the very beginning, we felt that the New York World’s Fair should not only celebrate a great event of the past, but should look to the future as well. The event we celebrate is, of course, the formal beginning of orderly democratic government in the United States — when million of men begin to co-operate in building their world —which is now our country.

The theme which inspires the Fair projects the spirit of this event into the future. It is a theme of building the World of Tomorrow—a world which can only be built by the interdependent co-operation of men and of nations.

Housed inside the Perisphere was Democracity: the planned city of tomorrow. It was organized “for the use of the people”, included a green belt and satellite towns for 1.5-million occupants, and was created by Henry Dreyfuss, an innovative human-centred designer that, among other things, designed the Hoover vacuum cleaner. From the pamphlet:

What we want is a great place to live in. We want to be proud of our city, not because we live in it, but because it is good to live in. Here it is…and we like it. It’s attractive and sensible at the same time. It’s pleasant because we’ve spent a lot of money to make it so…. At a low-tax rate too – because we haven’t wasted money.

As visitors sat in the revolving ring that hung over the model city, they could hear the narrator’s voice:

A brave new world built by united hands and hearts. Here brain and brawn, faith and courage are linked in high endeavor as men march on towards unity and peace. Listen! From office, farm, and factory they come with joyous song. Men working together … bound by a common faith in man … bound by their need of one another … free, independent men, knowing they can be free only because others help them to keep their freedom … independent and therefore interdependent. … Only such men and women can make the World of Tomorrow what they want it to be … a world fit for freeman to enjoy.

Democracity was designed to bring joy to its inhabitants. By cutting down working hours and the length of the commute to work, it was meant to increase its occupants’ leisure time. With buildings made of fireproof material and with transit functioning so perfectly, the police would be free to deal with “real” crime – although “The life of Democracity offers no incentive to crime.”

Oddly, it is entirely unclear how democratic Democracity is, and to what degree were its citizens involved in its design, if at all. The vision underlying it sounds like a mixture of Charles Fourier and Soviet propaganda. While the brochure makes a point that the City of Tomorrow is “Not fanciful … and not dictatorial” it also makes it clear that order is essential for its utopian ideal to materialize: “The City of Tomorrow which lies below you is as harmonious as the stars in their courses overhead—No anarchy—destroying the freedom of others—can exist here”.

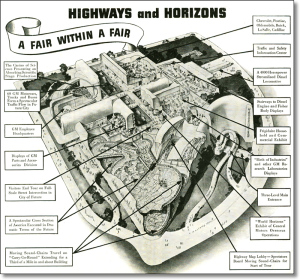

The Fair’s most popular exhibit was Futurama – a moving car ride located inside General Motor’s “Highways and Horizons” pavilion. It was created by Normal Bel Geddes, an industrial designer known for his streamlined style. Zooming up and down through the largest city model ever built, visitors would get a glimpse of the “wonder world of 1960”.

Describing the ride for The New Yorker, E.B. White wrote that it “induces approximately the same emotional response as a trip through the Cathedral of St. John the Divine”. Here’s the pavilion’s promotional film, To New Horizons.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1cRoaPLvQx0

When visiting the Fair White suffered from sinusitis, spurring the following observation: “When you can’t breathe through your nose, Tomorrow seems strangely like the day before yesterday”. This may account for the sarcasm that bursts through his account of what he called a “twentieth-century bazaar”. His favourite exhibit was AT&T’s pavilion, which he describes like this:

It took the old Telephone Company to put on the best show of all. To anyone who draws a lucky number, the company grants the privilege of making a long-distance call. This call can be to any point in the United States, and the bystanders have the exquisite privilege of listening in through earphones and of laughing unashamed…. I listened for two hours and ten minutes to this show, and I’d be there this minute if I were capable of standing up.

So even the origins of Facebook can be traced to the World of Tomorrow circa 1939.

Bonus: Salvador Dali’s installation from the Fair, Dream.

Fascinating report in Psychology Today about research that found affinities between dreaming and political orientation. The report notes that,

Those who identify as politically liberal tend to recall their dreams more frequently than those who identify as conservative. Additionally, conservatives tend to report more mundane dream content, whereas liberals have more bizarre dreams.

The report goes on to state that

These findings seem to suggest that liberals may differ from conservatives not only in their social values, but may be more imaginative than conservatives.

Although the report doesn’t clarify whether being liberal causes people to be more open to experience and dream more, or vice versa (dreamers become liberals), it got me thinking about the relation between our capacity to dream and our willingness to engage in transformative social action, something that has long occupied the Left. Walter Benjamin, for instance, describes modern life as the inhabiting of a capitalist dreamworld, the world of the “ever new”, where affect-driven, always-in-the-now experience is evoked and then invested in the continuous consumption of commodities. To dream, in this context, effectively insulates us from realities undergirded by exploitative labour relations, the destruction of nature, and so forth.

Yet for Benjamin, paradoxically, what allows us to break free from this slumber-like state is our capacity to dream alternative realities. In a world characterized by the accelerated channeling of creative energies into the valorization of commodities, only a change of pace can yield new thought patterns. That’s why the flâneur, walking the streets of Paris in a leisurely manner, ostensibly outside the rustle and bustle of capitalist production, was so important to Benjamin, as was boredom –”the dream bird that hatches the egg of experience. A rustling in the leaves drives him away”. For Benjamin dreams describe both a state of being, and the means to break out of it.

(a dialectical image? with thanks to Shane Gunster)

If utopias are images or stories that flesh out ideal futures, what are real utopias (besides being an oxymoron of sorts)? Erik Olin Wright’s answer is that they are “alternatives that can be built in the world as it is that also prefigure the world as it could be”. In his lecture, sponsored by The Institute for the Humanities at Simon Fraser University, Wright pours content into the definition with concrete examples – real utopias that “embody, in varying degrees, the values of equality, democracy, community and sustainability to a greater extent than does capitalism”. In a sense, the cases collected in Chris Turner’s The Geography of Hope can also be seen as instances of real utopias, and, for my work, the affinity with design fiction is clear.

I am delighted to take part in Disruptive Imaginings – a weeklong workshop/retreat on Wasan Island (Ontario), dedicated to collaboratively thinking about how we may imagine, experience, and bring about a better future. Lots of distinguished participants (and I look so young in that 10 year-old pic!), and very exciting activities. Can’t wait till the end of the month!